"Julia Ann Wilbur". Haverford College Collection, Haverford College, Pennsylvania.

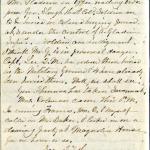

Wilbur, Julia Ann, Diary, May 5, 1864. Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, accessed May 2018.

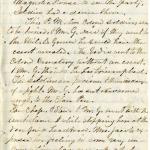

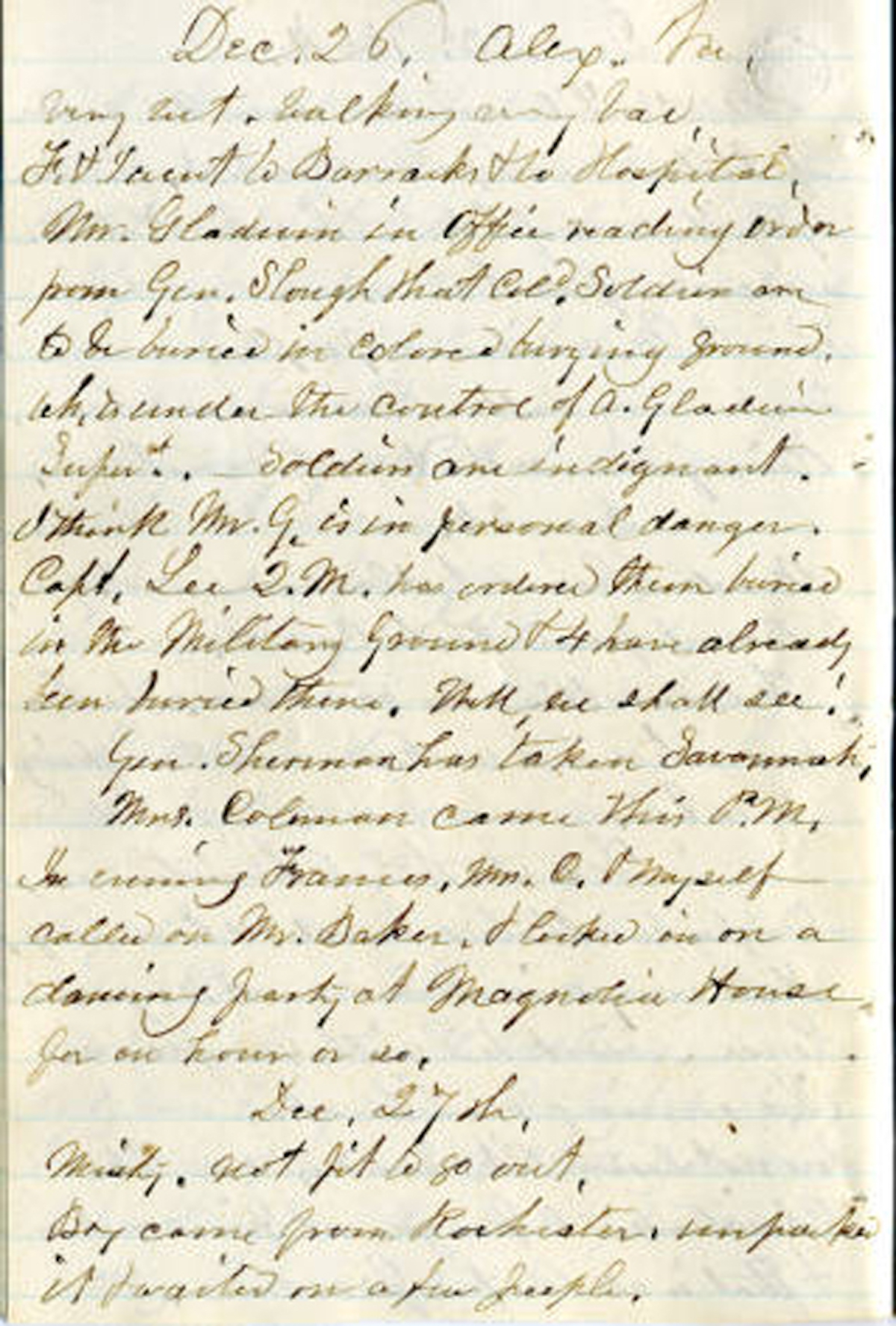

Wilbur, Julia Ann, Diary, December 26, 1864. Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, accessed May 2018.

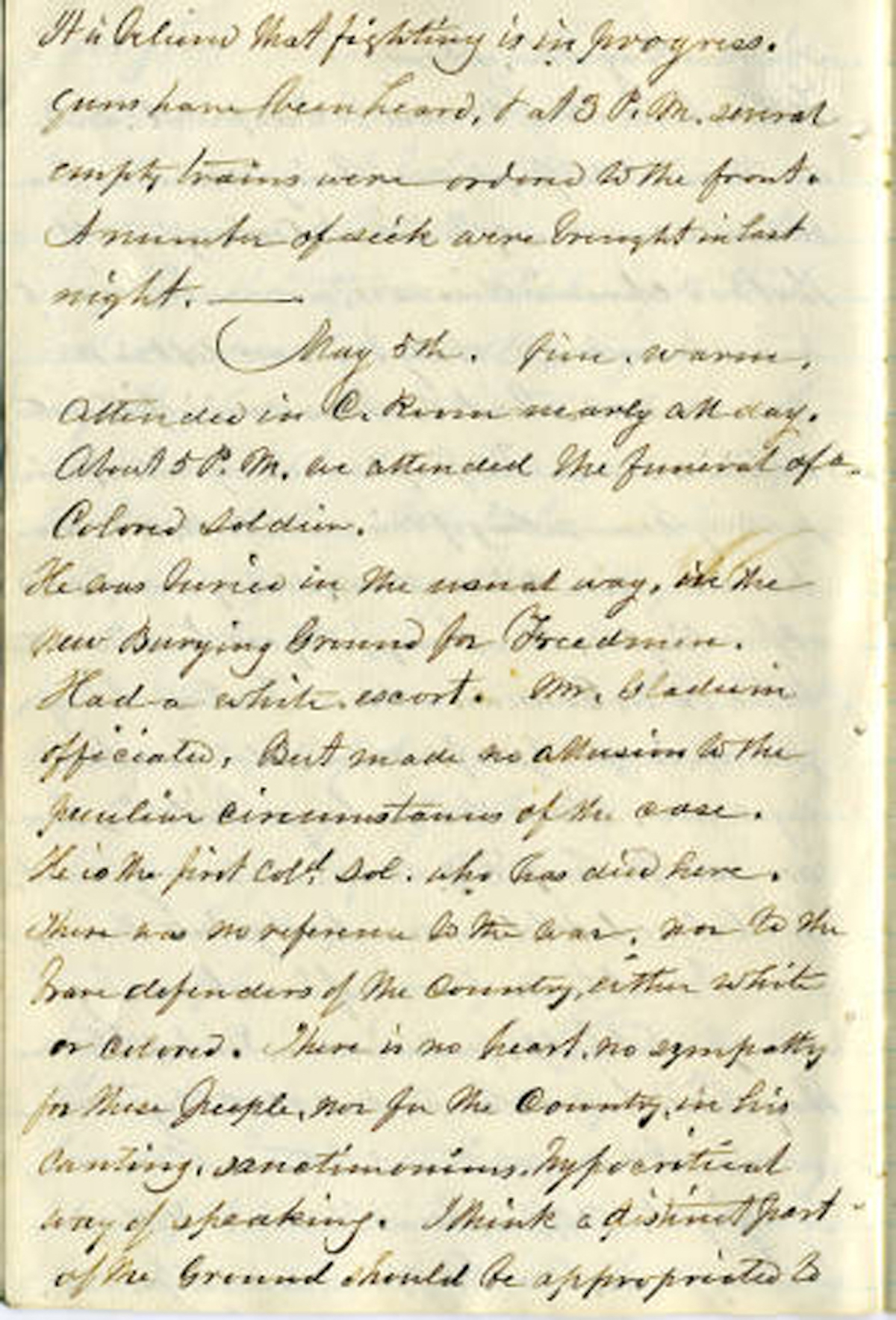

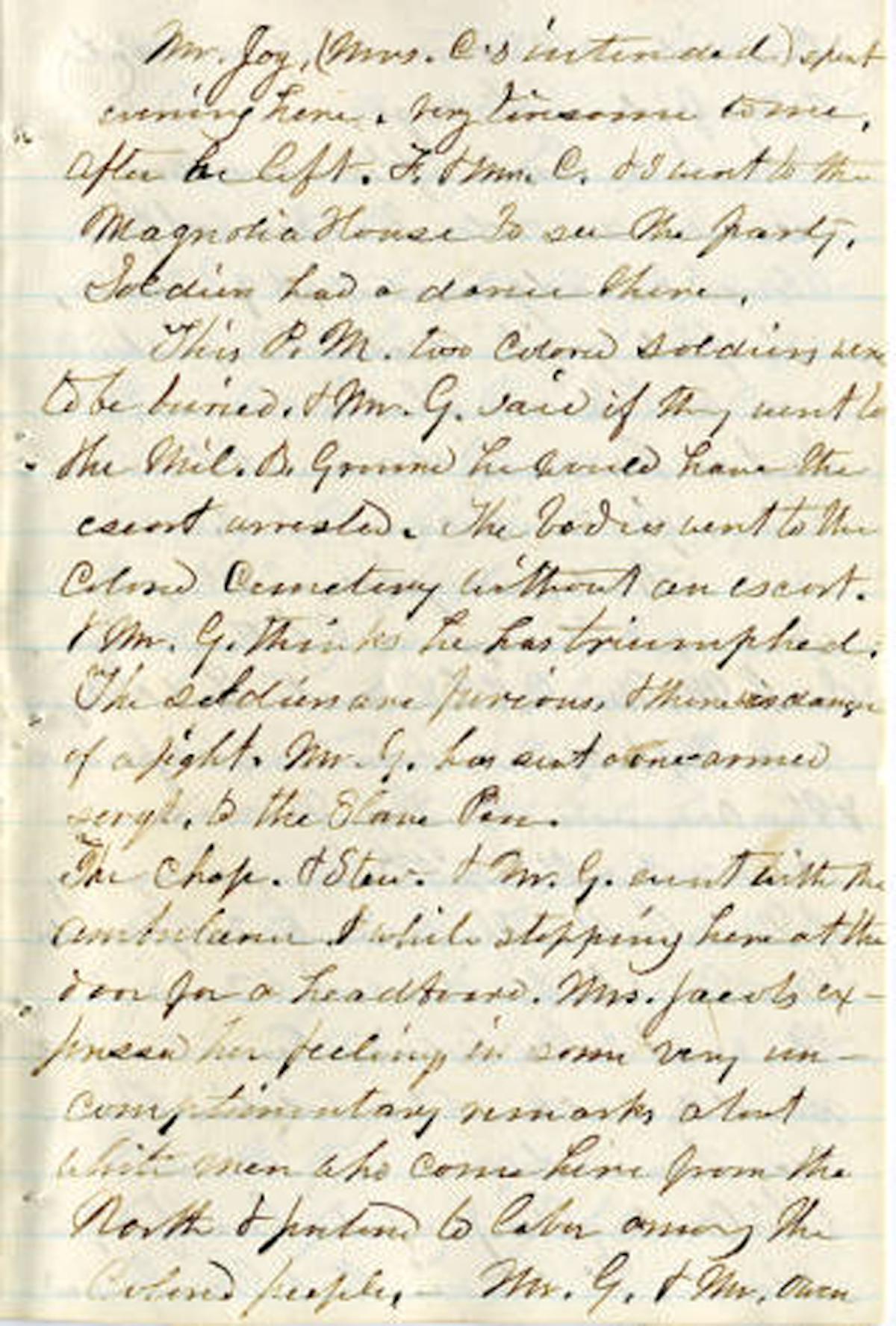

Wilbur, Julia Ann, Diary, December 27, 1864. Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College, accessed May 2018.

[May 5, 1864] About 5 P.M. we attended the funeral of a Colored Soldier. He was buried in the usual way, in the new Burying Ground for Freedmen. Had a white escort. Mr. Gladwin officiated. But made no allusions to the peculiar circumstances of the case. He is the first Col[ore]d. Sol[dier]. who has died here. There was no reference to the war, nor to the brave defenders of the country, either white or colored. There is no heart, no sympathy for these people, nor for the country, in his canting, sanctimonious, hypocritical way of speaking. I think a distinct part of the Ground should be appropriated to the soldiers, & theiy graves should be distinguished from others. They should be honored in some way. But we can’t make Mr. G. see it.—

[Dec. 26, 1864] F[rancis] & I went to Barrack’s & to Hospital. Mr. Gladwin in office reading order from Gen. Slough that col[ore]d soldiers are to be buried in colored burying ground, wh[ite] is under the control of A[rmy] Gladwin Super[intendent]. Soldiers are indignant. I think Mr. G. is in personal danger. Capt. Lee Q.M. has ordered them buried in the Military Ground & 4 have already been buried there. Well, we shall see!

[Dec. 27, 1864] “This P.M. two colored soldiers were to be buried. & Mr. G. said if they went to the Mil[itary] B[urial] Ground he would have the escort arrested. The bodies went to the Colored Cemetery without an escort. & Mr. G. thinks he has triumphed. The soldiers are furious. & there is danger of a fight.”

Julia Wilbur's Diary

The city of Alexandria was home to several cemeteries. The United States government oversaw Alexandria National Cemetery, called Soldiers’ Cemetery, where white soldiers were buried. In 1864, Captain James Lee, Assistant Quartermaster for the Quartermaster Corps, supervised this national military cemetery. Reverend Albert Gladwin, an African-American Free Baptist Minister from Connecticut, oversaw the Freedmen’s Cemetery, a cemetery established for contraband and freed African Americans in 1864. Julia Wilbur, an abolitionist from Rochester, NY, worked with Reverend Gladwin to provide support and supplies for newly freed African Americans in Union occupied Alexandria.

The debate over which cemetery to bury the U.S.C.T. was contentious because it had no precedent. As part of the military, these men were no longer runaway slaves, contraband, or freedmen; they were soldiers.

Reverend Gladwin, Captain Lee, and the military governor, General John P. Slough, responded differently to how U.S.C.T. should be buried. Wilbur’s diary recounts the back and forth she observed throughout 1864 between those who wanted to bury the Colored Troops with other federal troops and those who believed the U.S.C.T. should be buried with African Americans. Wilbur’s diary entries reveal who agreed with whom as well as different incidents when the men used their power and influence to force what they thought was correct.